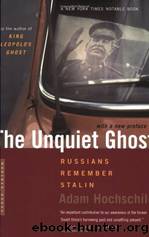

The Unquiet Ghost: Russians Remember Stalin by Adam Hochschild

Author:Adam Hochschild

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

Tags: New

Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Published: 0101-01-01T00:00:00+00:00

10. Paths Not Taken

While gulag survivors have begun to tell their stories, and researchers have explored mass graves and labor camp ruins, historians and writers have been arguing about the causes. Why did those years after the Russian Revolution that were supposed to usher in the radiant future for all humankind turn, so quickly, into such a disaster?

For other mass murders, the explanations seem simpler. The white settlers of the nineteenth century who killed American Indians and natives of Africa wanted land. The Nazis who killed Jews wanted scapegoatsâfor the losses of World War I, the humiliation of the Versailles Treaty, and ruinous inflation and unemployment. But the Soviet Union's rapid devouring of 20 million or so of its own citizens remains more mysterious. The scale is so vast, the grievances so ill-defined, the accused villains so omnipresent, and the madness so extreme: "We must execute not only the guilty," said Nikolai Krylenko, Lenin's Commissar of Justice. "Execution of the innocent will impress the masses even more." Indeed it would. But where does this kind of thinking come from?

Historians in the United States and Europe, of course, have had decades to argue over such questions. But among Russians, today's discussion has a pent-up intensity to it, because for hundreds of years, scholars could not debate in full freedom. In Russia the historian's profession has never been an easy one. "God ... merely decrees the future," Prince Kozlovsky said in 1839, "the Tsar can remake the past." Or, as one Soviet historian commented more recently, "The trouble is, you never know what's going to happen yesterday."

With the coming of glasnost, historians at last were able to speak openly about what did happen yesterday. One woman I met remembered the excitement of the first such talks, in 1987: "All Moscow was there in that small, miserable room. We fought our way through crowds, crawled under vehicles, to get to [historian Yu. S.] Borisov's lectures on Stalin. It was March or April, and it was still cold. Some journalists jumped in through the windows. People were outside, perched on the roofs of cars and on boxes, looking in through the windows."

Now that Russians can argue freely, they have staked out several major positions in the debate over the country's history. The crispest summary of them I heard came from Nikita Okhotin, head of historical research for Memorial. We were talking in a tiny, unheated office next to a room heaped with dusty piles of old newspapers, books, and documents, an apt symbol of a history that had not yet been sorted outâthe makings of what will become Memorial's Moscow library.

"Right now," Okhotin said, "we have a set of myths about our past. The most widespread myth is the Solzhenitsyn myth. That is, Russian history was the history of an outstanding country, a great country, which suddenly, in 1917, experienced a disaster. Then there are variations of this: The Bolsheviks are to blame; the Jew-Masons are to blame.

"A second position is that things were always pretty bad.

Download

The Unquiet Ghost: Russians Remember Stalin by Adam Hochschild.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Spell It Out by David Crystal(35852)

Life for Me Ain't Been No Crystal Stair by Susan Sheehan(35539)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32068)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31463)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31413)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(30794)

Professional Troublemaker by Luvvie Ajayi Jones(29425)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18641)

Twilight of the Idols With the Antichrist and Ecce Homo by Friedrich Nietzsche(18305)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18196)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(14773)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(14772)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(13790)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13692)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12923)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(12888)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(12848)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11957)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(11844)